~vidak

[email protected]

Statecraft and Totalitarianism

I recently had the chance to discuss more concrete and prefigurative politics with the ASF-Perth.

We decided the evidence supports the devolution of society into units of no more than around 200 people--around several hundred, in, perhaps exceptional circumstances.

This gave me pause for thought: the totalitarian aspect of the statecraft of the Federal Commonwealth of Australia was immediately cast into deep relief for me. Gone would be the days of largely sedentary, state-bank-backed mortgagee life.

Indeed parts of ASF-Perth have had some further opportunity to reflect on the nature and history of totalitarianism. One comrade recently expressed a definition of totalitarianism that was met with a great degree of approval from members and those in affinity to us.

This was that totalitarianism is the organisation along mass lines for the coercive use of violence--usually State sanctioned or motivated violence for the protection of a hierarchy which privileges some class of people over everybody else.

I think the Libertarians (i.e. anarchists) have it right when they attempt to broaden and deepen the definition and analysis of totalitarianism. I think it would be fair to say anarchism counts virtually all nation states as totalitarian in some way or another.

Statecraft and Empiricism

Something else I have been reflecting on is the frequently cited but just as frequently misunderstood nature of much of the Western Enlightenment philosophical tradition.

I recently had the opportunity to read some discussion between international and nationally-based comrades about anarchism would regard "Law", or the "Rule of Law".

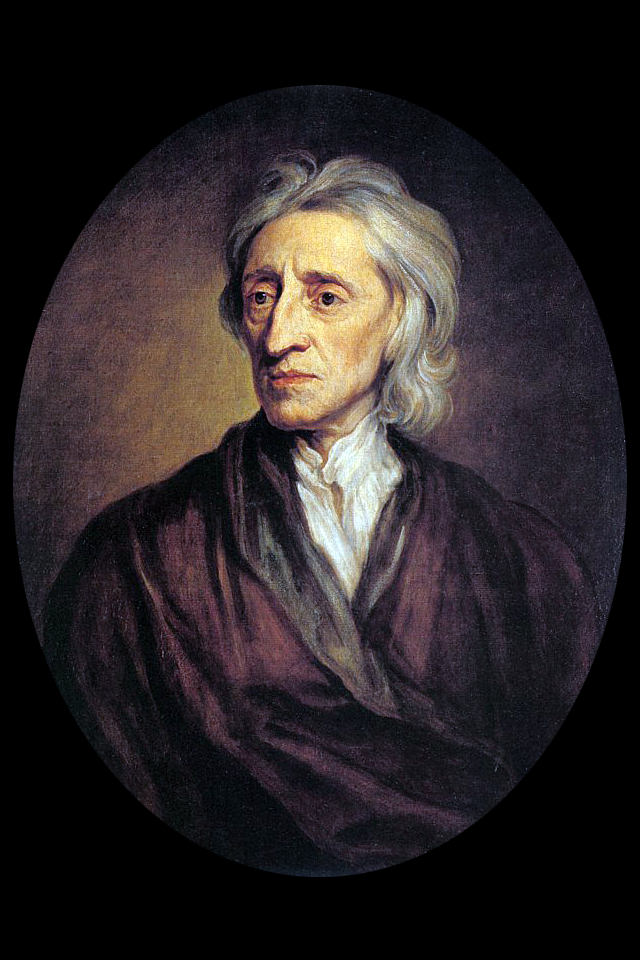

The bourgeois character of much of Enlightenment, Kantianism, and Cartesian Rationalism has always been something I have always been aware, but I have had the time to revisit Locke a little lately--the famous English Empiricist who, among other claims, asserted conscious identity was merely intuitively demonstrable, and distinguished between primary and secondary qualities--something to be ruthlessly

and rigorously pushed to its maximum logical absurdity by Hume.

I maintain much of these still-popularly studied philosophies are idle trivialities. Perhaps we could applaud Locke for his political writings, which were to go on to inspire the bourgeois American (1775) and French (1789) Revolutions.

My point is--why do we still popularly focus on the individual as a perceiver, instead of some radically less relativist explanation for Truth? The intersection between classical liberalism and, shall we also similarly say the 'classical' empiricists is not without its own ironies.

There is, for instance, something of the beginnings of socialism--or what we could more specifically say the original meaning behind the label 'social democracy'--within Locke.

Locke did indeed consider the then counter-factual possibility of the enclosure of all the world's land into private property:

As much land as a man tills, plants, improves, cultivates, and can

use the product of, so much is his property. He by his labour does,

as it were, inclose it from the common. Nor will it invalidate his

right, to say every body else has an equal title to it; and

therefore he cannot appropriate, he cannot inclose, without the

consent of all his fellow-commoners, all mankind.[^1]

[1]: John Locke (1690) Second Treatise on Government s 32.

And much of the moral economic argument for syndicalism/unionism probably finds much approval, if not its original genetic parenthood in Locke:

The labour of his body, and the work of his hands, we may say, are

properly his. Whatsoever then he removes out of the state that

nature hath provided, and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with,

and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his

property.[^2]

[2]: Ibid., s 27.

Practice; Action.

So what I am suggesting when I say we should part ways with epistemological individualism?

First, I say we should adopt a practical view with respect to how we treat the empirical data from our senses. That is not to say ears could not comprehend a beautiful sonata; what I am saying is that the metholodigcal individualism of much of what poasses for serious philosophy on epistemology today is overly theoretical.

When I was a member of Socialist Alternative, I was surely ready to be ejeccted when I asserted that Practice came before Theory. The context of the dicussion was the social regurgitation session among the SAlt members about the history of the lead-up to the Leninist ascession to power in October 1917.

We were asked--why were the others besides the Bolsheviks wrong about how to conduct a revolution?

My response--that perhaps the others had poor practical skills--was summarily rejected and repeatedly condemned.

Perhaps the concept of Theory-Before-Practice is able to be comphrehended popularly. In this case I will not elaborate on that point. But what I do mean when I say that the knowings of humans are fundamentally and exclusively originally Practical?

There is already a term in philosophy which embodies some other meaning but shares the same label for what I am about to name this epistemology.

Pragmatism; Voluntarism.

Put simply, the orthodox meaning of pragmatism in English-speaking philosophy is a metaphysical thesis about Truth that whatever is True is what is useful to one's own current logical activity. This is obviously true of the Pragmatism I want to develop, but it is not sufficient for my own term. Perhaps I could better name my

competitor epistemology to empiricism something even more arcane: 'Voluntaristic Materialism'.

I would characterise much epistemology as quite adequate at elaborating soundly on how people can "know that" but most classical empiricisms I would deem as having failed at explaining how conscious creatures can also "know how".

That is, epistemologies that focus on the passivity of knowing or sensing cannot explain how these knowers are spurred to activity. Perhaps they could describe, albeit purely passively, the logic embodied in some empirically proved activity. But the rational process also observable in human actions would remain sundered from it.

You have another pathway which you can take. And this is non-passive epistemology. Indeed I would characterise this philosophy as a kind of "voluntarism". This is not to create a philosophy of maximum absurdity. I am not trying to say that you can merely know or naturally perceive anything you wish.

This is also not a relativistic philosophy. What I mean when I say we should embrace voluntarism aout how we perceive the world is that we should assert that, in addition to Practice trumping Theory in terms of foundational for human perception, conscious creature are primarily DOERS instead of mere KNOWERS.

It is as if we have broadened the set of what counts as knowable. In addition to mere passive perception--which is also an activity--we also include active activity.

Locke might have dreamed that pirvate--in its proper sense, as singly-exclusively private--property could be conferred along with the mixing of consciously-directed manual or intellectual labour.

I would reverse the terms to give a more accurate appraisal of our currently advanced-age capitalism: PRIVATE PROPERTY CONFERS LABOUR.

And, as I have said above. I feel free to reverse te terms of traditional empiricist philosophy: KNOWLEDGE IS AN ACTIVITY.

Anarchy is order, but what is 'law'?

If we ground the concept of political obligation in 'rule-following', then we have to specify exactly what constitutes understanding a 'rule'. Any representationalist explanatio for how people come to internalise rules follows after Hobbes into 'absolutist' totalitarianism.

Why? Because we should be sceptical about social contract theories of the State. The only moral relationship their imagined social individual unit had to political obligations sanctified by a state is a Macchiavellian one.

It leads one to stand the concept of social obligations, as it were, on its head. There is a famous Stalinist joke that during an election, perhaps "it is the people who are wrong", and that an election serves to "dissolve them and elect another". This is the essential meaning when I say I agree that Australia is not actually a 'democracy'--it is in fact, a totalitarian state.

So, revisiting the concept of rule following with which we originally started, I say that is best thought of as "dispositions" or "rational habits". It should not be associated with any particular mental content. In fact the whole concept of mental content (NB. Paolo Freire's "banking theory" of education) has been thoroughly debunked, at its time is up.

There is an empiricist core to this non-deterministic and non-reductionist form of behaviourism. When we set out to 'find out what one is thinking', you do not actually consult another's 'ghost in their machine', with your own internal 'ghost'.

This is the origin of the modern popularity of the term. The idea that there is mental content is erroneous for the reason that is is a category error about the 'stuff' of ideas. It is as if each of us were a homunculus behind our retinas.

I suppose the big cultural upshot of what I am proposing to replace individualist philosophies of mind with, is that I suggest we purge much of our language and models of consciousness and replace them with this non-reductionist behaviourist model.

Indeed the story I have been telling is not just my own. I derived much of the inspiration for wht I call voluntaristic materialism from Wittgenstein through Gilbert Ryle.

The ability of Wittgenstein's slab movers in his Philosophical Investigations to communicate and cooperate through sheer immersion in a learned activity that had shaped their "dispositions" both.

Indeed I sat in on some instant-message discussion between comrades about the relationship of anarchism to the concept of the "rule of law".

In much the same was as I advocate for the purging of our language and culture of certain individualist philosophies--I would similarly purge the current conception of the "rule of law" of everything but the meaning that law is anything but a complex rational habit.

I think it could perhaps be argued--not by me--that there is a distinction between orderly cooperation through explicit rules, and "law", but I think the distinction has by that point become so fine-grained, I am not sure if disenchanting our language that far is necessary. That's (law) perfectly fine not to purge from our culture.

Perhaps the association of law with retributive justice--ie., law enforced with punishment--could inded be purged. Again, perhaps, revisiting an earlier theme of 'statecraft and totalitarianism' is a fruitful one.

Law, Anarchism, and Justice

Justice is perhaps also the more perfect term for a discussion of the concept of "law" and its relationship to the practice of anarchism.

For the consideration given above about the sized of associations under anarchism that we have earlier adduced could only really be several hundred in population at the very, very most--law under these units would look far, far different than the law that is currently exacted here in Australia, for instance.

Gone would be the totalitarian character of justice, I predict, under these sorts of conditions. But, still present would, or should be (I should say) the concept of explicit formal codified procedures for cooperation, under well-understood circumstances. it is also my understanding, and my hope, that these associations would be perfectly individually voluntary.

I will finish on the bizarre nature of the name I have given my metaphysics: voluntaristic materialism. I claim my insistence on the empirical observability of 'ideas' as 'dispositions' or perhaps channelling a little Aristotle--'rational habits' entitles me to count my philosophy as a materialist one. Why go further at mystification of social relations when they can easily said be empirically

observable.

As I may have already explained, the key element of the anti-representationalist nature of the philosophy of mind is that the 'mind'--if we should refer to it at all here--is an activity, and is future-orientated, and is intentional, relational, if not always goal orientated.

But the term voluntarism I chose because of my old tradition of Western Marxism. I was, after all, a Libertarian Marxist before I became an anarcho-communist. If we return to the individualism of the British Empiricists of Locke, Hume, Bacon, etc., the Western Marxists almost universally associate this with the bourgeois cultural millieu of classical Enlightnment philosophy.

And I agree with them. The Western Marxists took after Lukacs in discovering that bourgeois philosophy was riddled with contradictions. The deepest and most fundamental illogical flaw that the Western Marxists accused Bourgeois philosophy was the "antinomy" of contemplation and voluntarism.

Thus Kant’s ethical analysis leads us back to the unsolved methodological problem of the thing-in-itself. We have already defined the philosophically significant side of this problem, its methodological aspect, as the relation between form and content, as the problem of the irreducibility of the factual, and the irrationality of matter. ...

It is well known that Kant did not go beyond the critical interpretation of ethical facts in the individual consciousness. This had a number of consequences. In the first place, these facts were thereby transformed into something merely there and could not be conceived of as having been ‘created’.

Secondly, this intensifies the ‘intelligible contingency’ of an ‘external world’ > subject to the laws of nature. In the absence of a

real, concrete solution the dilemma of freedom and necessity, of

voluntarism and fatalism is simply shunted into a siding. That is to

say, in nature and in the ‘external world’ laws still operate with

inexorable necessity [22], while freedom and the autonomy that is

supposed to result from the discovery of the ethical world are

reduced to a mere point of view from which to judge internal

events. These events, however, are seen as being subject in all their

motives and effects and even in their psychological elements to a

fatalistically regarded objective necessity.[^3]

[3]: Georg Lukacs (1971, Trans. Rodney Livingstone) History and Class Consciousness p 125-127.

Empiricism was passive and conservative, and voluntarism was to be indentified with rationalism. Kant embodied the antinomy most perfectly in one persons's whole philosophy.

The Western Marxists may have been very conservative about the results and achievements of 'voluntaristic' philosophies. I say if we re-orientated our understanding of how our senses actually work-ie. are always engaged in practical activity--then I feel we must embrace the idea that we are not mere passive observers of nature, but are always already immersed in complex social relations that are themselves also active.

Western Marxists also typically replaced the concept of the individual as a historical subject of agencies with more mass-oriented class analyses which were sometimes antiquated and quite rigidly totalitarian.

But I, after dwelling on the Western Marxists over the years, saw that they had not meditated at all on the concept of authority of hierarchy. Indeed Lukacs was to pen a serious philosophical tract in support of Leninism.

Georg Lukacs (1924) Lenin: A Study on the Unity of his Thought.

I take Gilbert Rule and the Later Wittgensteinians to really be onto something with their materialist philosophy of anti-representationalism.

Conclusion

Statecraft and Totalitarianism

We see that statecraft is more or less always an attempt at totalitarianism--the, perhaps, homogenisation of society through retributive-only models of justice: ie., coercion and violence.

Anarchism and Political Obligations

I argue that the anarchist should not shy away from practicing the 'rule of law', but this understanding or practice of 'law' must be informed by voluntaristic materialism. For example: law does not need to be based on bourgeois principles--States versus the individual perceiver as the generalisable model upon which political systems are constructed.

Anti-Representationalism

The 'mind' we each sentient creatures possess is a "doer" rather than merely a "knower". We had to understand experience ecologically, and understand intentionality as a complex, open, system.